Managing invasive non-native grey squirrels to safeguard our native red squirrels and woodland biodiversity

An invasive non-native species (INNS) is one that has a negative impact on the environment, economy or our health and our way of life. Globally, INNS are one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss, contributing to 40% of animal extinctions that occurred in the last 400 years.[1]

There are 30 invasive non-native animal species listed as a concern in the UK because of their invasiveness and ability to establish successfully, often to the detriment of native species[2]. Those considered widely spread include grey squirrel, muntjac deer, signal crayfish and terrapins.

For example, American mink escaped or released from fur farms in the early 1900’s were the direct cause of the 94% decline in native water vole range in the UK. Only through decades of successful mink management programmes has it been possible to reintroduce water voles in areas of Northern England[3].

“Invasive non-native species not only challenge the survival of some of our rarest species but damage our natural ecosystems as well as costing the economy more than £1.7 billion per year. The law requires management measures to be put in place …[4].” – Minister for Rural Affairs and Biosecurity, Lord Gardiner. Each INNS has a story and impacts our native wildlife one way or another.

Grey squirrel impacts

Grey squirrels have a significant effect on biodiversity with woodland habitats and some species specifically affected by them, including our native red squirrel and woodland birds. Grey squirrels compete with red squirrels for food and transmit squirrel pox virus, which is fatal to reds but not greys. Research published in the Journal of Animal Ecology that competition from grey squirrels causes increased chronic stress in native red squirrels, which has an impact on their ability to reproduce and thrive.[5]

Grey squirrels also cause significant damage through bark-stripping broadleaf trees exposing timber to fungal and insect attack and impacting our woodlands’ reproductive resilience. Woodlands also play a valuable role in carbon sequestration that is impacted if trees are damaged or killed.[6]

Graham Taylor, Chair of the European Squirrel Initiative and managing director of Pryor and Rickett, estimates that grey squirrel bark stripping accounts for over £40 million in losses from the forestry industry. “These figures are alarming and in economic terms a disaster for those woodland owners who are not taking effective steps to control grey squirrels,” Graham said, “this must be a wake-up call to all those involved in owning, growing and managing our woodland, including the Forestry Commission and government, to ensure that proper steps are taken to insure this damage is prevented.” [7]

Grey squirrels also damage people’s property. The British Pest Control Association receive over 1,000 enquiries a year from the public looking for professional services relating to squirrel control.[8] The total estimated impact on the economy, in England alone, is estimated to be as much as £64 million per year. [9]

Managing grey squirrels

Research demonstrates there are a range of economic benefits from managing invasive species, including safeguarding biodiversity, reducing losses from forestry and agriculture, and improving ecosystem health. [10]

The grey squirrel remains of great concern and is included in the IUCN’s international list of “100 worst invasive non-native species”.[11] Red squirrels are conversely listed as ‘endangered’ on the recent Red List for Britain’s Mammals.[12]

A recent study highlighted there being little public knowledge on the negative impacts of grey squirrels. Contrary to the notion of it being a problem species, the presence of grey squirrels is often desirable as it one of the most common wild mammal species the public encounter in parks and woodlands. [13]

Although accounts of damage to buildings are occasionally reported, grey squirrels are seldom regarded as a nuisance in urban areas. The wider public therefore may not share the same negative experiences with grey squirrels as those involved in woodland management or conservation, and many may be totally unaware of the need to manage their populations. [14]

While the killing of one species to conserve another may be contentious in some circumstances, studies found this not to be a notable barrier to involvement from volunteers in communities where red squirrels do occur. This is perhaps because of a heightened understanding of the need for management and an affection for their local red squirrels. Those in red squirrel areas are significantly more knowledgeable about squirrel issues and their management, value reds significantly more, and consider grey squirrel controls to be significantly more acceptable relative to the wider population.[15]

Management methods

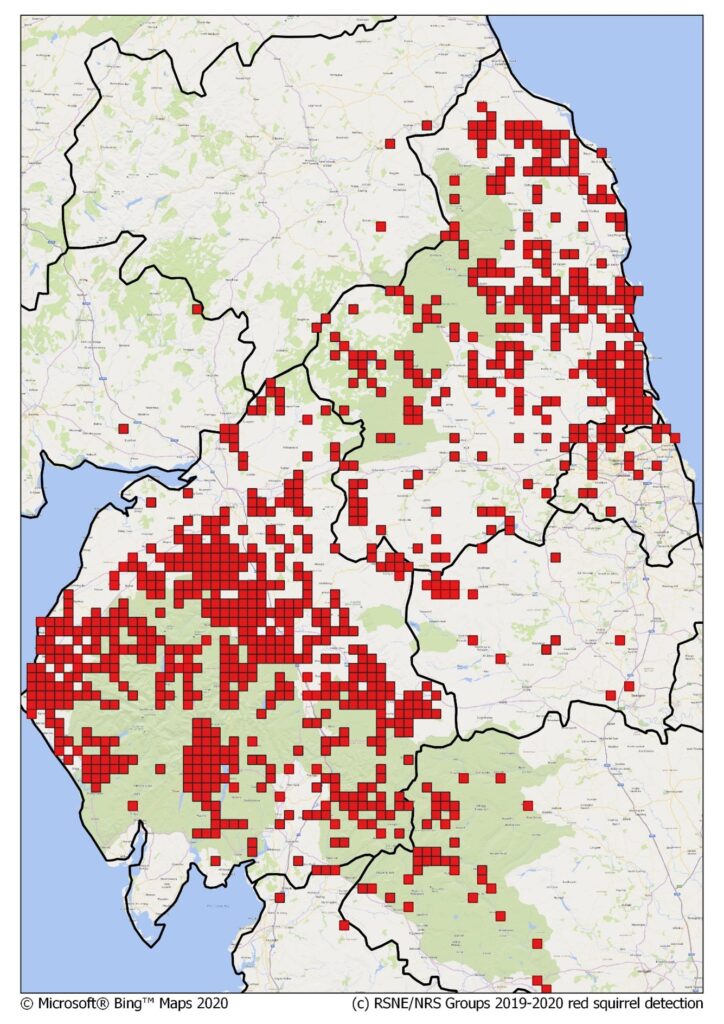

Survey results from one of the biggest citizen science projects in mammal conservation in the UK[16] has demonstrated that the collective conservation action, mainly (80%+) through the efforts (i.e. lethal grey control) by local volunteer groups[17] has turned the tide in favour or red squirrels (see map below). This is mainly due to the active suppression of grey squirrel populations across the region, which is an ongoing battle that needs to be sustained. It is well demonstrated that thus far any preventative action to manage grey squirrels other than lethal control has tried and failed.

While the use of traps, shooting and drey poking (the disturbance of a nest with a pole) remain common forms of grey squirrel management, research to develop and deliver a non-lethal fertility control method is now also being championed by the UK Squirrel Accord[18] in collaboration with the Animal and Plant Health Agency. Ecological modelling suggests that fertility control alone is unlikely to achieve a rapid reduction in grey squirrel populations. “However, when applied to the low-density populations following short-term culling, eradication could be achieved within the same timescales as continuous culling alone but with substantially lower costs.”[19]

It is evident that community support of red squirrels is crucial to the success of their conservation. The challenge is to communicate the unfortunate necessity of lethal grey squirrel management, alongside future fertility control, to those living outside red squirrel areas as a means of protecting this native species.

- Is it acceptable to do nothing, bearing in mind there are no alternative methods at present, and to permit the loss of native biodiversity, including our treasured red squirrels?

- Is it acceptable to abandon reds to suffer the deadly consequences of squirrel pox virus?[20]

- Is it acceptable to not act to remedy a human-induced problem impacting other species?

These are serious questions to be considered.

There are thousands of dedicated and vital volunteers, who already ascribe a significant value to their local red squirrels, passionate about devoting substantial periods of their time on tasks, such as monitoring and grey squirrel management (in excess of 20,000 person hours per year). Their affinity for the red squirrel is the main reason we are still fortunate enough to be able to enjoy this charismatic and entertaining species in areas of the UK today.

Heinz Traut completed a Conservation and Forest Ecology (BSc) degree at Bangor University, exchanging a high-flying career in busy London for a more meaningful career in conservation. Although a qualified forester, red squirrels were waiting for him in the Lake District, where he was employed as RSNE surveyor in 2012; followed by a 2½ year stint in Dumfriesshire with Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels. In 2014 he returned to RSNE as part-time Project Officer and in 2020 has picking up the reins as RSNE Project Manager.

[1] https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/blog/2019/05/invasive-species/

[2] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/invasive-non-native-alien-animal-species-rules-in-england-and-wales

[3] https://www.nwt.org.uk/what-we-doprojects/restoring-ratty

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/invasive-species-order-2019-consultation-opens

[5] Grey squirrels cause increased chronic stress in native red squirrels (Issue 36, Nov 2018, page 7). https://www.europeansquirrelinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ESI-Squirrel-Issue-36.pdf – Accessed: 18/01/2021

[6] European Squirrel Initiative (2019) https://www.europeansquirrelinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/40-MILLION-PER-ANNUM-TIMBER-LOSS-FROM-GREY-SQUIRRELS.pdf – Accessed 19/01/2021.

[7] European Squirrel Initiative (2019) https://www.europeansquirrelinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/40-MILLION-PER-ANNUM-TIMBER-LOSS-FROM-GREY-SQUIRRELS.pdf – Accessed 19/01/2021.

[9] European Squirrel Initiative (2019) https://www.europeansquirrelinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/40-MILLION-PER-ANNUM-TIMBER-LOSS-FROM-GREY-SQUIRRELS.pdf – Accessed 19/01/2021.

[10] Nick Hanley1 | Michaela Roberts2, 2019. The economic benefits of invasive species management. British Ecological Society: People and Nature.

[11] Mike Dunna,?, Mariella Marzanoa, Jack Forsterb, Robin M.A. Gillb, 2018. Public attitudes towards “pest” management: Perceptions on squirrel management strategies in the UK. Biological Conservation 222, 52–63.

[12] https://www.mammal.org.uk/science-research/red-list/

[13] Mike Dunna,?, Mariella Marzanoa, Jack Forsterb, Robin M.A. Gillb, 2018. Public attitudes towards “pest” management: Perceptions on squirrel management strategies in the UK. Biological Conservation 222, 52–63.

[14] Dunn, M., Marzano, M., Forster, J., 2021. The red zone: Attitudes towards squirrels and their management where it matters most. Biological Conservation 253.

[15] Dunn, M., Marzano, M., Forster, J., 2021. The red zone: Attitudes towards squirrels and their management where it matters most. Biological Conservation 253.

[16] RSNE Squirrel Monitoring Programme page – https://www.rsne.org.uk/squirrel-monitoring-programme

[17] Northern Red Squirrels volunteer umbrella group map – http://www.northernredsquirrels.org.uk/nrs-groups/member-groups-map/

[18] https://squirrelaccord.uk/squirrels/fertility_control/

[19] S. Croft *, J.N. Aegerter, S. Beatham, J. Coats, G. Massei, 2021. A spatially explicit population model to compare management using culling and fertility control to reduce numbers of grey squirrels. Ecological Modelling 440 (2021) 109386.

[20] http://www.northernredsquirrels.org.uk/squirrels/squirrel-pox-virus/